When we first meet Jennifer, the protagonist of Coralie Fargeat’s Revenge (2017), she’s sucking suggestively on a lollipop. This suggestive act serves as foreshadowing; within minutes she will be enthusiastically performing fellatio on her lover. After focusing on her lollipop sucking, the camera’s gaze shifts to Jen’s hot pink, micro-miniskirt and the long, tan legs that spill out of it. Immediately, Fargeat uses these shots to establish how Jen is viewed, and that’s as a sex object, first and foremost.

These male-gazing shots and the oral sex scene all happen before Jen has even spoken a word of dialogue. Her male companion Richard is ostentatiously wealthy, married, and clearly sees Jennifer as a little more than a plaything. As the film begins, he’s whisking her away for a secret tryst at his secluded desert home. Soon though, his two oafish friends show up unexpectedly and take a disturbing, leering interest in the only woman in the house.

Jen seemingly enjoys that the men are ogling her body. She dances in a skimpy bikini poolside as the two men salivate. These early scenes establish her as young and naive, highly sexual, and even courting the male gaze. Farageat emphasizes Jennifer’s objectification with a slew of gratuitous shots lingering on her body, especially her backside. The film invites us to objectify Jennifer also, implicating us alongside the film’s three male characters. She is a piece of ass, on display and ready to perform—the men see her as little more than a sex doll in a bikini and hot pink star-shaped earrings, to be used and discarded as they see fit. And that’s exactly what they do.

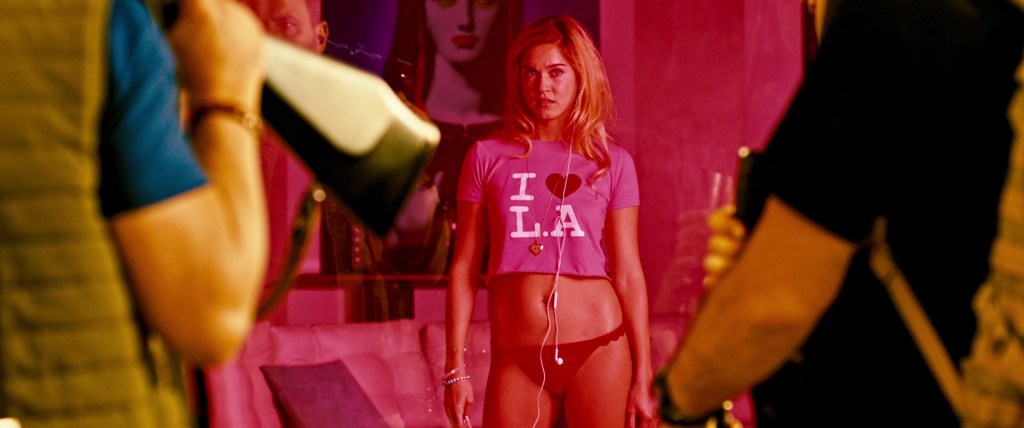

Revenge works so brilliantly as a rape-revenge film precisely because Fargeat so masterfully sets the scene in those early moments. When Jen’s eventual degradation occurs, it feels particularly devastating. She is a good-time girl who wears a two-sizes too-small “I ❤️ LA” crop top. In no way is she prepared for what these men have in store for her. One of Richard’s creepy friends find Jen alone and rapes her, utilizing the age-old defense for sexual assault by saying that she was “asking for it” with her provocative outfits and behavior. The other man turns up the music to drown out her screams. It’s a sudden violation, made all the more powerful because up to this point we the audience have been seeing Jen through the objectified lens the men see her through.

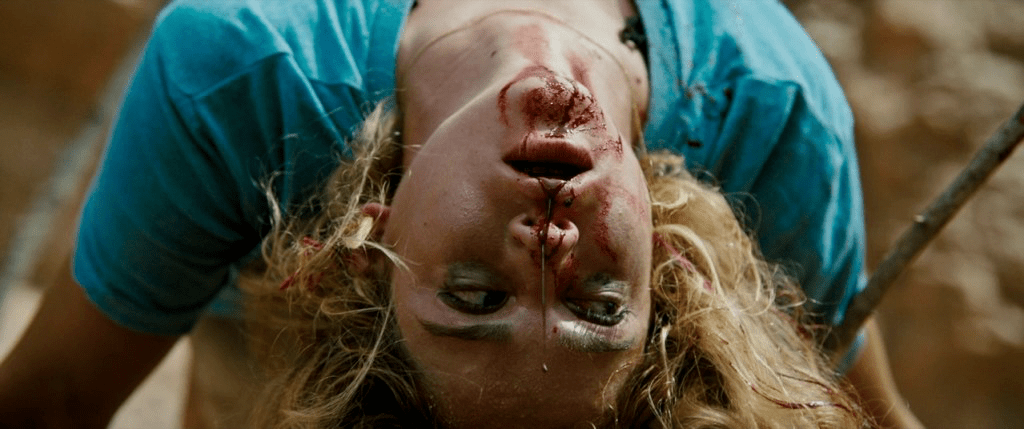

After finding out what happened, Richard is no help. He simply offers Jen a job so she’ll keep her mouth shut about the assault. When she refuses to be bribed, he shows his true colors and shoves her off a cliff to her presumable death. Yet, she does not die. This is when the film transforms from a standard rape-revenge thriller into a tale worthy of myth. Impaled on a tree, and left for dead, Jen manages to extricate herself and, with a tree branch still impaling her midsection, stumbles to safety to regroup. Soon, through some combination of fear, adrenaline, and the hallucinatory effects of some peyote she had stashed away, Jen is waging a an all-out revenge mission against the three men.

At one point, she finally removes the impaled branch, stanching the open wound with a heated beer can, which leaves behind the beer’s logo—a mythical Phoenix taking flight. Jen is now the Phoenix. This fantastical shift works because Fargeat is telling a tale worthy of a mythic treatment. Jennifer’s transformation from a lollipop-sucking victim to a resurrected desert-warrior with sudden combat skills works both because of the tropes associated with the rape-revenge genre and also because Fargeat transcends them in ways few similar films have.

When Revenge shifts to the revenge portion of its rape-revenge structure, so does Fargeat’s approach to how we view Jennifer and her body. Gone are the shots that objectify her legs, mouth, and ass. Still, during this extended portion of the film, Fargeat cannily keeps Jen in an outfit—bikini bottoms, a makeshift sports bra, and those hot pink star earrings—that would traditionally be seen as objectifying. Flipping the script, Fargeat’s lens now invites us to view Jen’s body as fierce and powerful. Weapons and ammunition that she collects along the way are strapped to her body. No longer pretty in pink—note the scene when Jen’s rapist first confronts her while she stands behind a pink window pane, afraid and exposed—now she’s covered in sand and blood, a determined scowl replacing the flirty smile from earlier in the film.

Reborn as a lethal killing machine, Jen methodically and intelligently tracks the men through the desert, one by one. Preyed upon and seemingly left for dead, the hunted is now the hunter. This is where the carnage begins, and Fargeat doesn’t shy away from the gore. With cinematographer Robrecht Heyvaert, Fargeat takes full advantage of the stunning Moroccan landscapes, painting the desert sand red with bloodshed. They also frame Jen as a warrior, stoic and composed, grim and determined. It’s no surprise Fargeat has said in interviews that she was inspired by films like Mad Max and Rambo, where protagonists embark on “phantasmagoric” journeys. Interestingly, Panos Cosmatos’s Mandy (2018), which came out the year after Revenge, also portrays a mythic, phantasmagoric hero’s journey for Nicolas Cage’s character. While those films centered on men seeking revenge, Revenge positions a woman as the avenging angel, as in Abel Ferrara’s excellent Ms. .45 (1981).

Ms. .45 feels like an apt comparison to me in that neither film seeks to exploit their main characters. The sexual assaults in both films are presented as horrible, traumatizing acts, as they should be. In some ways then, Revenge comes from the 1970s–1980s glut of B-movie rape-revenge films, but in other ways it moves beyond the genre. Fargeat’s filmmaking is expert and assured, the production values are high quality, and the performances from an international cast are uniformly believable. All of the male actors are exceedingly good at playing vile sociopaths, but it’s Italian actress and model Matilda Anna Ingrid Lutz as Jen who carries the weight of Fargeat’s impressive debut feature. Lutz is extraordinary in a physical role that calls for her to do much of her acting without dialogue, instead revealing Jen’s emotions through her eyes and mannerisms. Early in the film, Lutz’s eyes radiate sex and vitality. After her near-death experience, those same eyes harden into a steely glare that’s positively mesmerizing. It’s a fearless performance, worthy of the highest praise.

With Revenge, Coralie Fargeat utilized the framework of an exploitation film—the rape-revenge plot—to create something powerful and artistic that actually has something to say about the way women are treated. Late in the film, during their final confrontation, Richard taunts Jen, “Women always have to put up a fucking fight.” He doesn’t know how right he is. Throughout her journey from victim to warrior-survivor, Jen never stops fighting. Ultimately, watching Jen’s transformation journey is what makes Revenge such a cathartic experience, and a modern film classic.

Absolutely brutal but brilliant feminist revenge thriller. Loves it when i saw it in the cinema 5 years ago

LikeLiked by 1 person

I loved this film as well Michael 🙂 Speaking of which, the director of Revenge is Coralie Fargeat. According to her wikipeida entry, she is a fan of the two Davids – David Cronenberg and David Lynch – much like myself 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

And much like me, too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great minds think alike 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person