Among film lovers, Nancy Allen is considered a capital “G” Goddess. A central figure in late 1970s, early 1980s American cinema, Allen is revered thanks to her performances in at least six classics films with rabid fanbases: Carrie (1976), I Wanna Hold Your Hand (1978), Dressed to Kill (1980), Blow Out (1981), Terror in the Aisles (1984), and Robocop (1987). She’s worked with acclaimed directors like Steven Spielberg, Brian De Palma, Paul Verhoeven, and Steven Soderbergh. For those of us that grew up seeing Allen’s movies in the theater, and/or renting them repeatedly on VHS, she was as prominent in our lives as some family members.

She’s excellent in each one of the films mentioned above—her performance in Brian De Palma’s Carrie is iconic—but today I’m here to bow down to her glory in De Palma’s notorious erotic thriller, Dressed to Kill. Allen plays Liz Blake, a high-priced call girl ensnared in a murder mystery that makes her the killer’s next target. After meeting with a client, Liz stumbles upon a brutally murdered woman in the elevator—previously, we had been following this woman for the film’s bravura opening act (and she’s played by a stunningly vulnerable Angie Dickinson), Liz soon partners with the victim’s son Peter (Keith Gordon) as amateur investigators trying to solve the case. It’s all very reminiscent of giallo, with De Palma ratcheting up the tension to nigh-unbearable heights as our amateur detectives get in way over their heads.

Allen and Gordon are terrific as the film’s odd couple: a brash-taking, seen-it-all prostitute, and a grieving, introverted tech geek. When the police don’t believe Liz, because of her profession, she teams up with the revenge-minded Peter. He brings the technical savvy, using various homemade listening devices and time-lapse cameras to monitor their suspect. After some sleuthing, Liz eventually acts as the bait the pair needs to snare a killer.

Liz puts her life on the line to confront the prime suspect (played by Michael Caine). Part of the plan involves distracting him to get at some potential incriminating documents, so Liz strips down to sexy lingerie—the male fantasy girl in black bra and panties, with garter belts and thigh high stockings—and initiates a raunchy exchange:

Liz Blake: Do you want to fuck me?

Doctor Robert Elliott: Oh, yes.

Liz Blake: Then why don’t you?

Doctor Robert Elliott: Because I’m a doctor and…

Liz Blake: Fucked a lot of doctors.

Doctor Robert Elliott: …and I’m married.

Liz Blake: Fucked a lot of them, too.

Liz doesn’t stop there, declaring, “Well, because of the size of that cock in your pants, I don’t think you’re so married.” During this astonishingly frank scene—it almost feels lifted from a porno—Allen provides the jaw-dropping sizzle, while Caine plays it close to the vest, subtly revealing the good doctor’s struggle to resist Liz’s carnal temptation.

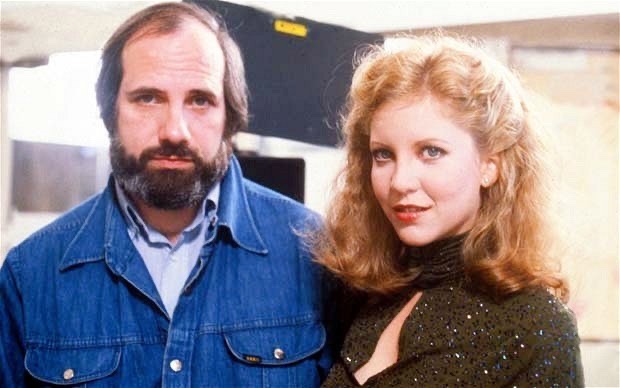

Dressed to Kill was Allen’s third of four films with De Palma in a five-year period—plus she was married to him at this point. This scene had to be a vulnerable one for Allen to perform. You wouldn’t know it—acting!—because she seems utterly comfortable while lounging in lingerie on a desk and delivering blush-inducing dialogue with gusto.

Liz is a stock character type—the intrepid hooker with a heart of gold who says things like “Thank god, straight fucks are still in style!”—but Allen imbues her with so much heart and soul that she transcends the stereotype. It’s a marvelous performance, melding aspects of classic Hollywood style with the grittier, New Hollywood style of that era. You could imagine Allen playing this sort of part in an early 1950s noir just as easily. Its one of her best, most fully realized performances.

As much as I’ve tried to offer clever analysis here, I haven’t done nearly as exquisite a job discussing Nancy Allen’s strengths as Megan Abbott did did for Metrograph when she explored the actress’s key role in De Palma’s ouevre. The entire piece is spectacular, but especially when Abbott’s dissects Allen’s work in Dressed to Kill, about which she writes,

Making full use of her sing-song voice, her big eyes, and that glorious nimbus of curls, Liz performs a series of ideas of womanhood for all the men in the film: whore, fantasy object, professional woman, surrogate mom, fantasy girlfriend, Nancy Drew in a garter belt. She can “do” them all, revealing each for the construction it surely is.

Abbott positions Nancy Allen as the perfect focal point for which to observe the often-troublesome, but never boring, sex and gender politics of De Palma’s films:

It is in Allen’s performances that we see the trickiness of De Palma’s play with gender and sex in full, fulsome flower. She is in fact his greatest envoy in the sex wars. She embodies all his work’s contradictions and somehow renders them glorious, delectable, meaningful.

Ultimately, that’s why film lovers appreciate Nancy Allen so much, even forty-odd years after these brilliant performances. She “embodies” the “glorious, delectable, meaningful” work of a director like De Palma; she seems to fully understand the work as well as the director does. In a challenging role, in a tricky film like Dressed to Kill, she’s fully committed to the work and delivers a charismatic and uninhibited performance.